Mafia: The Game of Information Asymmetry

If you have ever played the game Mafia with a group of friends, you understand the game revolves around one group knowing information another group does not – a concept called information asymmetry. Some people may also know the game as Rebels vs. Spies or Werewolf, but the concept behind the game mechanics remains the same. This paper theoretically analyzes the players and coalitions in this partial information environment.

At its core, the game consists of two teams – a large number of citizens and a smaller number of mafia. During the night phase, the mafia eliminate a player from the game; during the day phase, players vote to eliminate a player as a suspect. These phases continue until the mafia players are eliminated or the mafia players outnumber the citizens. Essentially, the objective of the citizens is to identify and eliminate the mafia, and the objective of the mafia is to eliminate all the citizens. Though variations in roles and gameplay exist, the analysis of the game in this post will solely consist of these two teams.

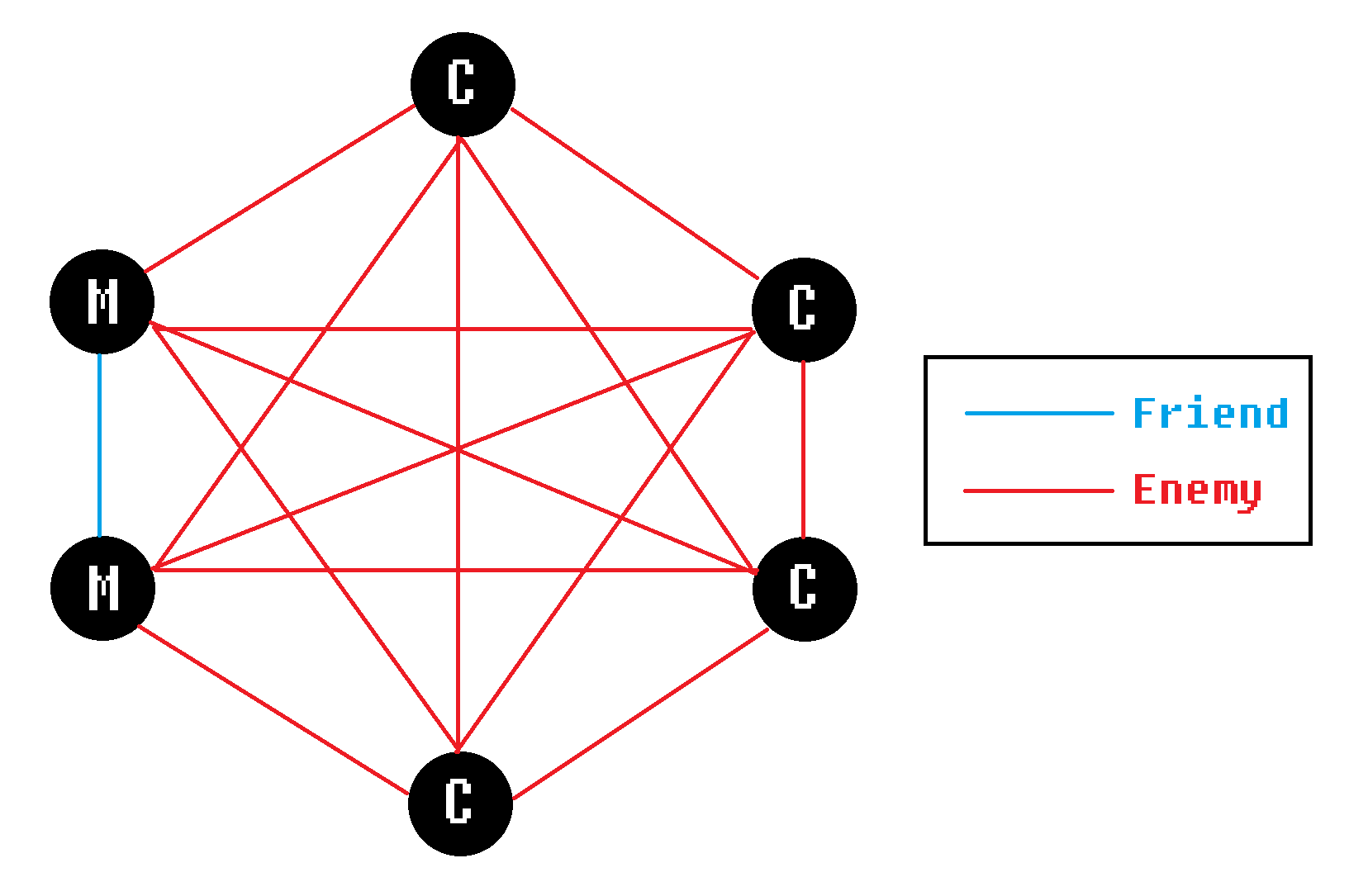

Though quite a complex game filled with deception and logic, the Mafia game can be simplified to a network of friends and enemies. The game begins with the following graph, where only the mafia players are friends with their fellow mafia players, and the citizens deem every other player an enemy since any person could be a mafia player:

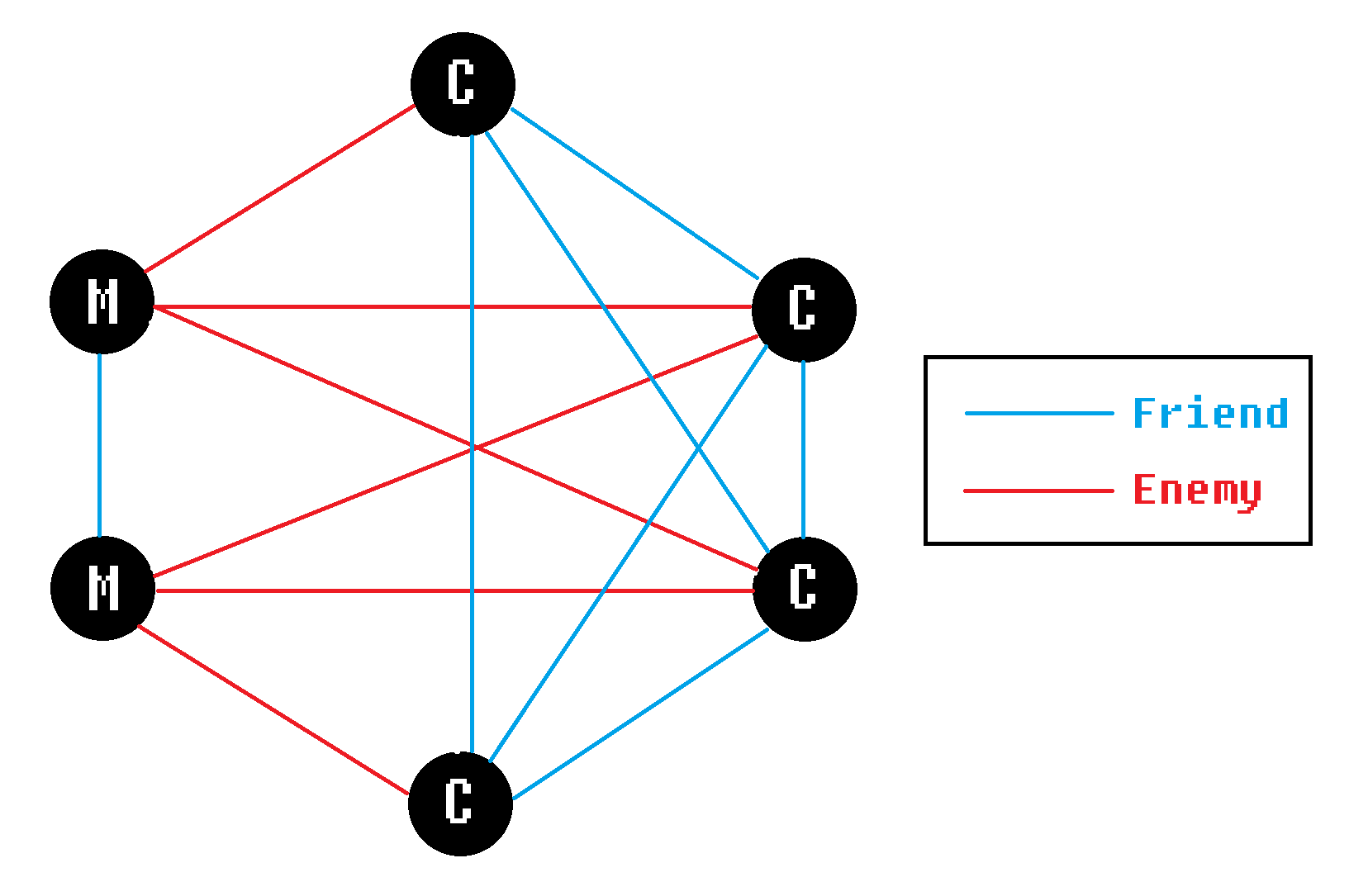

For the citizen players, the connections necessary for them to win consist of friend connections between all citizens and enemy connections to the mafia players, as follows:

From the mafia players’ points of view, any friend connection they make with a citizen player is beneficial to a mafia victory. As long as the day phase consists of the citizens making enemy connections with their fellow citizen players, the mafia win that phase.

However, the game is consistently dynamic in terms of who people think are the mafia and who are citizens, and this ever-changing component can lead to unexpected events and interesting developments. These characteristics are precisely relevant to the concept of information cascades. In the simple herding experiment created by Anderson and Holt in Chapter 16 of the Networks textbook, the model describes how some decisions are made when uncertainty is involved. The conclusions of the model demonstrate that:

1) odd decision patterns can occur (citizen players eliminate a fellow citizen player)

2) these cascades can lead to nonoptimal results (the rational logic of a citizen’s reasoning can lead to another citizen being eliminated during the day phase)

3) cascades are very fragile – even if it exists for quite some time, it can be effortlessly overturned (as soon as citizen players realize that a player is a mafia player, a shift in friend and enemy connections occurs immediately)

At first, the concept of the Mafia game is seemingly simple – two teams in which each team’s goal is to eliminate the other team. However, through the enemy-friend and information cascade analyses, one’s view on the game changes dramatically with this enlightened networks perspective. The next time you play, think about the ever-changing web of connections between players and what motivates a certain player to say what he/she said. Accounting for these subtleties may just win you your next game!