The history of planning is replete with theories reified in their heyday but then lose their sheen under the scrutiny of hindsight. From Howard’s Garden Cities to Corbusier’s High Modernism, the waxing and waning of planning “fads” seems to plague the legacy of the planning profession. Urban realities today have exposed the flaws of past planning movements, and given rise to new ones. There is hope, however, that city planners have improved in their assessment of obstacles and solutions to successful cities. This article synthesizes contemporary innovations in planning that present potentially more successful alternatives to problematic theories of the past.

- The car is the future

The Plan: Le Corbusier was among the most ardent of advocates of planning for a future of the automobile. In his landmark thesis Towards an Architecture (1924), he writes – “The motor car has completely overturned our old ideas of town planning” – and proceeded to postulate a city plan of super highways and skyscrapers set in parks[1] – “I tell you straight: a city made for speed is made for success.”[2] This principle, together with socio-economic transformations and mass consumerism, set the tone for car-centric city planning in America catalyzed by the 1956 Federal Aid Highway Act.

The Problem: A transport system built for cars has created streetscapes hostile to most other uses. Development in America has promoted an over-reliance on cars, because urban environments have not been designed for alternative lifestyles. Not only does this disadvantage those with limited access to automobiles, it has also been devastating to the environment. 15% of America’s greenhouse gas emissions come from the use of automobiles,[3] which amounted to about 1 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalents in 2013[4], equivalent to the amount of carbon sequestered by a forest more than one-third the size of the US.[5]

The Solution: Sustainable transport alternatives are in the limelight today, particularly non-motorized forms: walking and cycling. The Complete Streets movement advocates an about-turn in the legacy of American transportation planning – privileging the pedestrian and cyclist over the car.[6] Jeff Speck describes, in his book Walkable City, that streets need to be useful, safe, comfortable and interesting for pedestrians.[7] Some cities have gone even further, pushing cars out of the picture completely – Oslo is the first city to have planned for a car-free urban center, come 2019.[8]

- Suburbs are the American Dream

The Plan: Wright’s “Broadacre City” took decentralization beyond the small community imagined in Ebenezer Howard’s “Garden City” to the individual family home, each living his chosen lifestyle on his own land, with a network of superhighways joining together the scattered elements of society. He subscribed to the Jeffersonian idea of individualism, believing that individuality must be founded on individual ownership.[9] The roots of anti-urban individualism are reflected in the traditional American Dream, summarized in the single family suburban home: white picket fences, three kids, a dog, a two-car garage, open lawns, and neighborhood cookouts in the backyard.[10]

The Problem: American sprawl has been criticized for its environmental impacts linked to lengthy automobile-dependent commutes, as well as the impact of developing greenfield sites. In addition, suburbs are notoriously homogeneous, and play a central role as the destination of white flight in America’s history of racial spatial segregation. In The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jacobs derides “the extraordinary governmental financial incentives [that] have been required to achieve this degree of monotony, sterility, and vulgarity” – referencing the funds channeled towards the development of suburban sprawl, through policies such as the earlier-mentioned 1956 Federal Aid Highway Act. Single-family homes in suburban neighborhoods continue to disadvantage the socioeconomically marginalized, given the associated higher costs of home maintenance and transport.[11] Suburbs also continue to exhibit drastically less racial and nativity diversity than their city centers.[12]

The Solution: In her same book, Jacobs advocates the vitality and safety of dense city living. This concept has resounded with many contemporary planners, and more recently by economist Edward Glaeser, who redefines urban living as the American Dream, by arguing that cities make us richer, smarter, greener, healthier and happier.[13] City planning departments too today actively court residents back into the city center, targeting the young, working-age “creative class” in the hopes of re-establishing cultural and economic vitality.[14]

- Land is uni-functional

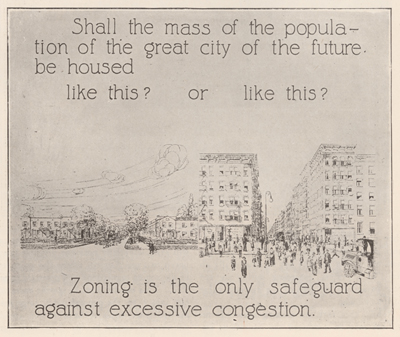

The Plan: America first formally introduced single-use zoning through the 1926 Standard Zoning Enabling Act.[15] Zoning was championed by then-Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover, who bemoaned that its absence had resulted in “enormous losses in human happiness and in money. … The lack of adequate open spaces, of playgrounds and parks, the congestion of streets, the misery of tenement life and its repercussions upon each new generation, are an untold charge against our American life.”[16] The solution was an attempt to simplify the chaos of the city – early Euclidean zoning assigned single, separated land uses to building lots, led by pioneers such as New York lawyer Edward M. Bassett, labeled “Mr. Zoning”, and Cincinnati native Alfred Bettman who defended zoning before the U.S. Supreme Court in Euclid v. Amber Realty (1926).[17]

The Problem: Cities soon found that single-use zoning was often over-simplistic and inflexible. Compounded by the politics behind land development, new zones were regularly created to accommodate cases that did not fit into the mold – which were many. City ordinances became overly cluttered, and the proliferation of land uses revealed the complexity of an issue planners had hoped to tackle through simplification and separation. Euclidean zoning lacked the flexibility to respond to the needs and rapid rate of evolution of the city.

The Solution: Contemporary planners have responded with New Urbanism, form-based zoning, and the SmartCode. New Urbanism was pioneered by Duany and Plater-Zyberk, who synthesized the ideas of Ebenezer Howard and Jane Jacobs to postulate a new model for urban development focused on the built form and based off detailed codes that require mixed use, mandate density, ensure orientation to the street, and provide detailed architectural guidelines to maintain a harmony among buildings.[18] While not without its faults, New Urbanism has responded to its critics to create urban environments that are more heterogeneous and inclusive.[19]

- It’s a numbers game

The Plan: The rational approach to planning has been employed since the onset of the profession, by planners seeking to put order to the chaos of the city. The rational design of social order is epitomized in what Scott terms “authoritarian high modernism,” espoused by planners such as Le Corbusier and implemented by administrators like New York City’s Robert Moses. They sought to apply science and technology to understand engineer cities, which often translated into huge slum clearance and urban renewal projects.[20]

The Problem: Rittel and Webber argue that the sphere of urban planning addresses inherently “wicked” problems that cannot be comprehensively solved via a straightforward rational approach.[21] Urban environments are more often unpredictable and incredibly nuanced, evidenced by the unforeseen outcomes of planning projects attempted with an authoritative arm of rationalism. One spectacular example is St. Louis, Illinois’ Pruitt-Igoe – a massive urban renewal project that invoked ‘slum’ clearance and the construction of modernist social housing, but failed as a consequence of its coincidence with post-war pro-suburban polices that impelled white flight and diminished the inner-city tax base, further exacerbating the poor financing structure of the project. It was demolished with explosives in the mid-1970s, barely two decades after its construction.

The Solution: Incremental planning, as postulated by Lindblom in response to the flawed “rational-comprehensive method” – the better method, he argues, is to acknowledge the inability of planning to comprehensively model and represent reality, and approach problems incrementally instead.[22] This overlaps with the incremental approach that Talen describes as an application of small-scale preservationist techniques to the existing city, “strengthening the existing urban fabric” by focusing on “daily life and the neighborhood.”[23] This technique has gained favor in contemporary times as opposed to the authoritarian methods of redevelopment applied in previous regimes. Dunam-Jones and Williamson have championed such a method for “retrofitting suburbia” to address its aforementioned ills.[24] One caveat however – at the same, the data revolution has reinvigorated the importance of the rational method and precipitated a trend of “smart cities” run efficiently by the analysis of big data.[25]

- Leave it to the experts

The Plan: Almost any planner with a name to his or her community plan may be quoted as an example, and even most plans headlined by government agencies similarly rely almost exclusively on “expert” opinion. Professionals have largely dominated the field of planning, born of the rhetoric that “if men of goodwill discussed a problem thoroughly, certainly the right solution would be forthcoming.”[26]

The Problem: As Davidoff (1973) explains, planning is a value-driven exercise and experts alone cannot represent the spectrum of values in a community.[27] Planning that relies on professional “wisdom” denies local knowledge, subverts the democratic process, and is an affront to equity in planning. By excluding citizens from the planning process, planners inevitably fail to capture needs and priorities on the ground. Even where citizens may be consulted – and often “consulted” is an euphemism for “informed” – Arnstein notes that “participation without redistribution of power is an empty and frustrating process for the powerless.”[28] This failure has been exposed by radical and insurgent forms of planning, where common citizens attempt to voice their stake and take unsanctioned steps to transform urban space through such actions as the “Occupy” movement.[29]

The Solution: Academics have argued for a transformation of the planning process to one that is necessarily inclusive and bottom-up. In his article Advocacy and Pluralism in Planning, Davidoff describes the need for diverse representation in planning, including assisting public interest groups in actively proposing alternatives to plans derived by official planning agencies.[30] Forester articulates the role of planners as facilitators of political deliberation amongst diverse stakeholders in the community.[31] Arnstein further explicates the various stages of citizen participation in planning, arguing that the ultimate form of participatory planning is where citizens are given control over decisions made in their community. This has been expressed in initiatives like participatory budgeting operating in various cities in Latin America that gives communities control over what common priorities to direct funds towards, such as infrastructural improvements or education. While there are obstacles to ensuring equity in this process, it has improved local government accountability and increased pro-poor expenditure. Planners have sought to reconcile such limitations of advocacy planning through equity planning, postulated by Krumholz, in which planning professionals take active steps to achieve equity objectives rather than leave it to the initiative of the grassroots.[33]

No planner can claim to have the panacea to urban ills. Contemporary strides in planning suggest that we have been improving in our assessment of and addressing of the promises and pitfalls of urbanism. Because of this, innovation can be considered an important indicator of how successful a new planning theory or policy is. We can only hope to have gotten it right, but if history proves otherwise, there will just have to be five more planners down the line to right our well-intentioned wrongs – hopefully not as drastically misdirected as the theories of some of our predecessors.

Works Cited:

[1] MIT Press. “The Automobile in Le Corbusier’s Ideal Cities.” Accessed on Nov 8, 2015. https://mitpress.mit.edu/sites/default/files/titles/content/9780262015363_sch_0001.pdf.

[2] Le Corbusier. (1987) City of Tomorrow and Its Planning (New York: Dover Publications). p. 190.

[3] USDOT. “Transportation and Greenhouse Gas Emissions”. Transportation & Climate Change Clearinghouse. Accessed Nov 11, 2015. http://climate.dot.gov/about/transportations-role/overview.html

[4] USEPA. (2015, Nov 4). “US Greenhouse Gas Inventory Report: 1990-2013”. Accessed Nov 11, 2015. http://www3.epa.gov/climatechange/ghgemissions/usinventoryreport.html

[5] USEPA. (2014, April). “Greenhouse Gas Equivalencies Calculator”. Accessed Nov 11, 2015. http://www2.epa.gov/energy/greenhouse-gas-equivalencies-calculator.

[6] McCann, Barbara. (2013) “Why We Build Incomplete Streets” in Completing Our Streets: The Transition to Safe and Inclusive Transportation Networks. p. 9.

[7] Speck, Jeff. (2012). Walkable City (New York: North Point Press). p. 11.

[8] Boyce, Russel. (2015, October 19). “Oslo aims to make city center car-free within four years”. Reuters Online. Accessed Nov 11, 2015. http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/10/19/us-norway-environment-oslo-idUSKCN0SD1GI20151019.

[9] Fishman, Robert. (1977) “Urban Utopias in the Twentieth Century” in Susan S. Fainstein and James DeFilippis (Ed.s), Readings in Planning Theory (New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons). pp. 30-31.

[10] Frizell, Sam. (2014, April 25). “The New American Dream is Living in a City, Not Owning a House in the Suburbs.” Time. Accessed Nov 9, 2015. http://time.com/72281/american-housing/.

[11] Salam, Reihan. (2014, Sep 28). “The Great Suburbia Debate.” National Review Online. Accessed on Nov 13, 2015. http://www.nationalreview.com/agenda/389018/great-suburbia-debate-reihan-salam

[12] Hall, Matthew & Lee, Barrett. (2008). “How Diverse are US Suburbs?” Urban Studies 41(1), 3-28.

[13] Glaeser, Edward. (2011). Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier and Happier (New York: Penguin Books).

[14] Florida, Richard. (2002). Rise of the Creative Class (New York: Basic Cooks).

[15] Ameriacn Planning Association. (2015). “Standard Enabling Acts.” Accessed Dec 1, 2015. https://www.planning.org/growingsmart/enablingacts.htm.

[16] Johnson, David A. (2015). Planning the Great Metropolis: The 1929 Regional Plan of New York and Its Environs (London: Routledge). p. 76.

[17] Knack, R., Muck, S. and Stollman, I. (1996). The Real Story Behind the Standard Planning and Zoning Acts of the 1920s. Land Use Law: 3-9. Accessed on October 31, 2015. https://www.planning.org/growingsmart/pdf/LULZDFeb96.pdf

[18] Fishman, Robert. “The Death and Life of American Regional Planning (Chapter 4)” in Bruce Katz (Ed.) (2000). Reflections on Regionalism (Washington, DC: Brookings). p. 66.

[19] Minner, Jennifer. (2015). CRP 2000 Lecture Week 8.

[20] Scott, James C. (1998). “Authoritarian High Modernism”. p. 56

[21] Rittel, Horst W. J. & Webber, Melvin, M. (1973). “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning.” Policy Sciences, 4. pp. 155-169.

[22] Lindblom, Charles E. (1959). “The Science of “Muddling Through””. Public Administration Review, 19. pp. 79-88.

[23] Talen, Emily. (2006). Connecting New Urbanism and American planning: an historical interpretation. Urban Design International 11. pp. 83-98.

[24] Fishman, Robert. “New Urbanism.” in Lawrence Vale, Bish Sanyal and Christina Rosan (Ed.s) (2012). Planning Ideas that Matter (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012). pp. 84.

[25] Townsend, Anthony M. (2013). Smart Cities: Big Data, Civic Hackers, and the Quest for a New Utopia (NY: W.W. Norton & Company).

[26] Davidoff, Paul. (1973). “Advocacy and Pluralism in Planning”. Journal of the American Institute of Planners 31 (4), pp. 544-55.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Arnstein, Sherry R. (1969). “A Ladder of Citizen Participation”. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35 (4). p. 216-224.

[29] Miraftab, Frank. (2009). “Insurgent Planning: Situating Radical Planning in the Global South”. Planning Theory, 8(1). pp. 32-50.

[30] Davidoff, Paul. (1973). “Advocacy and Pluralism in Planning”. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 31 (4). pp. 544-55.

[31] Forester, John. (1982). “Planning in the Face of Power”. Journal of the American Planning Association, 48. pp. 67-80.

[32] Souza, Celina. (2001). “Participatory budgeting in Brazilian cities: limits and possibilities in building democratic institutions”. Environment & Urbanization, 13 (1). pp. 159-184.

[33] Krumholz, Norman. (1982). “A Retrospective View of Equity Planning”. APA Journal, 42(2). pp. 163-174.