Cities are vibrant places, full of life and people carrying themselves each day through a state of ordered chaos. They are visual compilations of time, with old buildings and histories layered in and among the new. Perhaps the most fundamental change in the nature of the city was the transition to automobile infrastructure in the early twentieth century, allowing residents to live and work further away from the economic centers of the city than ever before. The creation of the quintessential American suburb is only a recent development, taking hold in the decades following World War II. During that time, inner cities saw declining residential, commercial, and industrial populations, and the resulting drop in tax revenues made them look to new innovative methods to coax Americans back.

Urban renewal was one such technique used by city governments to revitalize their downtowns. Capitalizing on a federal government with a new social prerogative, cities used federal subsidies for highway and housing construction to create new attractive areas in the place of neighborhoods still suffering from depressed economies and poor quality infrastructure (Zhang and Fang, 2004). These projects were grand in scale and destructive in nature, using the urban fabric as a blank page with which to implement new ideas of what a modern city should look like. The powers vested onto governments to complete these projects opened doors for various interests to take part in the political process, making original intentions complex and corrupt and implementation costly and laborious (Christensen, 2013).

Boston and Durham are two cities that experienced very different scopes and scales of urban renewal. In each, residents were displaced and economies altered under the promise of improving the greater public good, permanently changing the nature of the cities in which they were implemented. What was the final effect of these projects, and did they achieve their stated goals? Though they do not illustrate the true variety of projects that were implemented in cities across the South and Northeast, they reveal the nature of urban renewal as a fantastically powerful form of government action, for good and also for bad.

Boston’s West End

Since its founding in the early years of Colonial America, Boston has been a city of immigrants. Its West End neighborhood grew in the nineteenth century to become a stopping point for new immigrants to enter society, providing low rent housing in an economically vibrant area, providing a means for eventual economic mobility (Gans, 1959). Through this process, the West End played a vital public good for Boston’s larger economic and social population.

By the end of World War II, Boston was experiencing white residential, commercial, and industrial flight to the suburbs characteristic of northeastern cities of the era. Title I of the Housing Act of 1949 unlocked massive federal funding for housing redevelopment projects, specifically in replacing blighted areas in disrepair with adequate housing (Zhang and Fang, 2004). Key to the rationale behind this authority was the moral imperative of taking citizens out of blighted neighborhoods, as blight was seen as pathological and its removal a public necessity as to prevent derelict areas from causing the decline of surrounding neighborhoods (Gans, 1959).

Boston’s West End was cited as suitable for redevelopment by the Boston Housing Authority for its overcrowding, mixed residential and commercial uses, substandard housing stock, high rates of “indices of bad environment” like juvenile delinquency and tuberculosis, and low quality schools and services (Boston Housing Authority, 1953). Less publicized was the high land value of the West End, located adjacent to downtown and the Charles River, and lobbying efforts by real estate interests hoping to get a bid in the redevelopment process were influential in the neighborhood’s targeting (Christensen, 2013).

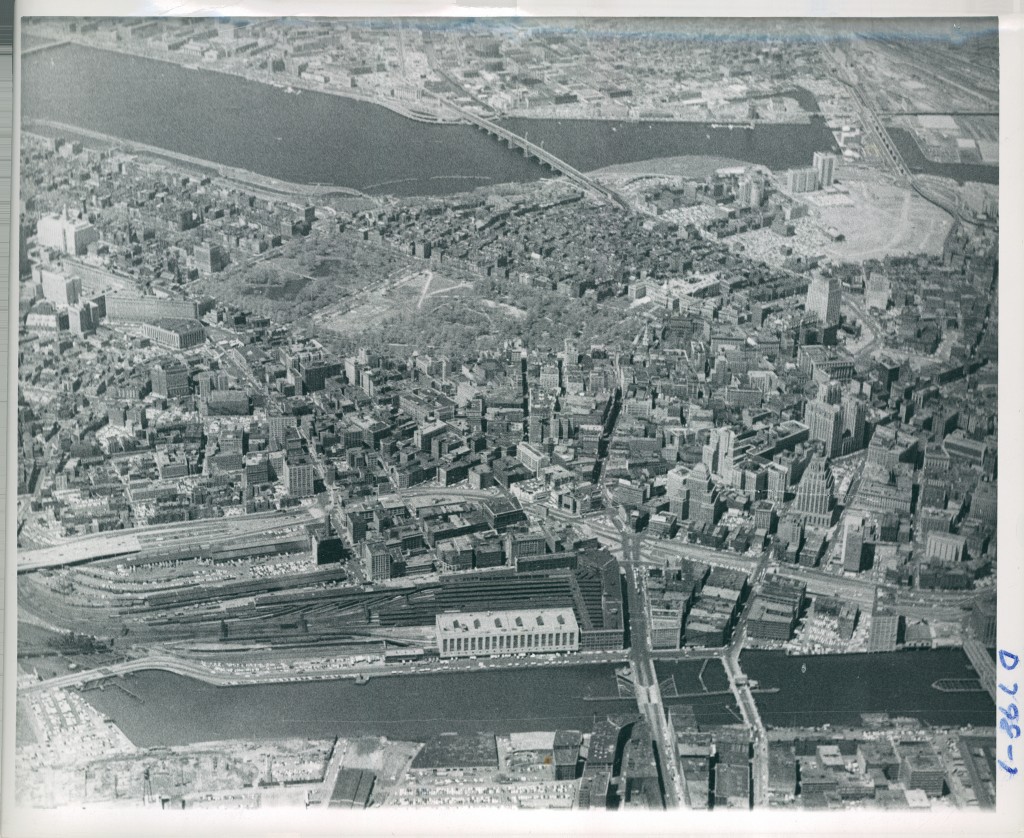

Boston’s West End can be seen in the top right as a large open space, after the demolition of its structures and relocation of its residents (Boston Redevelopment Authority, 1960).

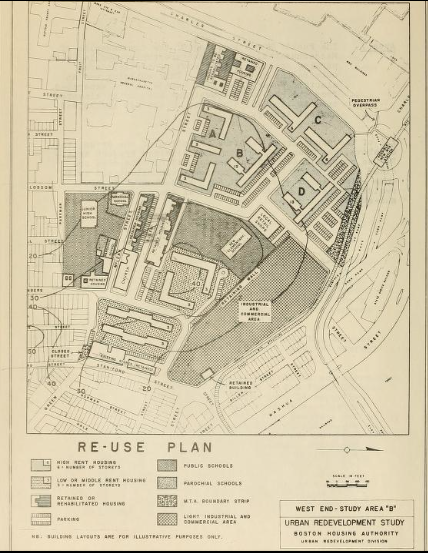

The Boston Housing Authority released plans for the neighborhood’s redevelopment in 1953. In the place of the West End’s narrow streets and three-story tenements, the proposal drew single-use zones separating residential, civic, and industrial uses and removed streets to create open “superlots” on which to build high-rise apartment complexes. As Christensen (2013) notes, this housing was not intended for current residents but for the middle classes that had left Boston for the suburbs; displaced residents would be relocated to public housing or reimbursed for private housing elsewhere in the city. The plan concluded with a bold statement that the whole process from land clearing to completion would take only three to four years.

Re-Use Plan from Boston Housing Authority’s 1953 redevelopment proposal. Note the size of the blocks and separation of uses compared to the older areas surrounding it (Boston Housing Authority, 1953).

The reality of the resulting redevelopment would challenge the Authority’s intentions and claim. Over 8,000 residents were displaced and 2,800 structures destroyed. The city claimed properties via eminent domain in 1958, seizing each property for $1. Herbert Gans (1959) found that the relocation procedures not only destroyed the culture of the West End but also separated extended families and caused irrevocable psychological damage to the displaced. Fearing the stigma and conditions of public housing, a tremendous number of residents rejected the option for relocation and demanded private housing subsidies, straining the government’s funds, saturating private housing demand, and placing hidden financial burden previously understood to be the government’s obligation on the citizens themselves. The process ended up spanning decades, with almost 10 years passing just between land clearing and construction, during which the land was leased as private parking (Christensen, 2013).

The West End today appears similar to the original redevelopment plans, with luxury high-rise apartments standing on green lawns and upscale shopping and civic centers scattered among them. What was lost was the neighborhood’s value as an agent of economic mobility and the cultural resources stemming from its close-knit community. The economic, social, and psychological effects of the relocation on its residents played a key role in the push for citizen input in the planning process, and in 2015 the Director of the Boston Redevelopment Authority officially apologized for its role in “destruction of neighborhoods and the displacement of residents.” The controversies surrounding the project would lead the Authority and many like it nationwide to use community feedback in plan goals, practice more nuance in the use of renewal tools, and show more transparency in the motives and processes of government projects (Boston Redevelopment, 2015).

Durham’s Hayti

Durham, North Carolina is a medium-sized city of 228,000 people, with about an even split between white and black residents (United States, 2010). Located in the Piedmont region of the state, the city was established in the nineteenth-century as an industrial center for tobacco processing. The booming cigarette business led by American Tobacco spurred the city to become a regional hub for commerce and culture. Hayti, the center of the city’s black economy, was the largest black neighborhood in Durham and was hailed as the “Mecca of black capitalism”, earning praise from both Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Dubois (Brundage, 2005). Though located near Durham’s city center, Hayti was separated by coal yards and rail lines, leading it to become a self-sufficient community serviced by independent black businesses.

Despite the economic center’s strength and the professionalization of many of its residents, Hayti was plagued by the poverty that was rampant among post-Reconstruction black communities. A 1916 survey showed that four of five blacks in the city lived in substandard rental housing, and white landlords helped block New Deal housing improvement funds to allow them to continue to control rents across the city (Brundage, 2005). By the 1950s, Durham had lost a sizable portion of its white population to the suburbs and the residents of Hayti had segregated themselves by class.

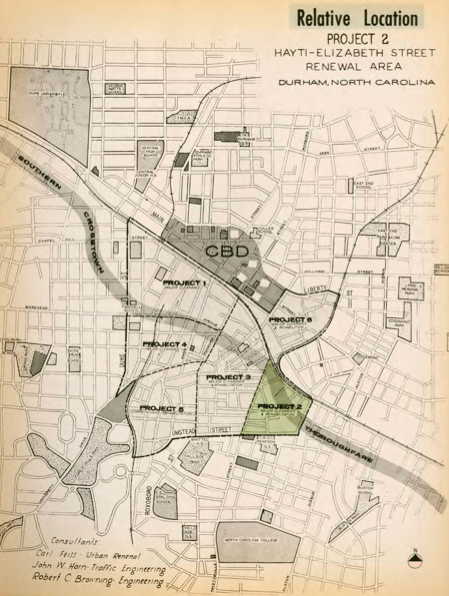

In an effort to revitalize the city’s tax base, depleted by the loss of commerce and profession following white flight, the City of Durham created a Redevelopment Commission in 1958 to capitalize on generous federal subsidies (NC Civic, n.d.). The primary element of this commission’s plans was the construction of a highway connecting I-85 and I-40 with the intention of improving access into the city, relieving congestion, and spurring job creation and tax revenues. Additionally, the Commission was given the authority to buy land and relocate residents via eminent domain. Hayti, wracked by a lack of New Deal reinvestment and still suffering from the economic blows of the Depression, was cited for substandard housing stock and decrepit infrastructure, giving the Commission an opportunity to use its prime location in the city for redevelopment (Durham Redevelopment, n.d.). Interestingly, Hayti’s black elites supported the project for the expected property reinvestments yet neglected to tell residents about the plans to use the redevelopment to clear ground for the highway. A 1962 referendum actually passed as a result of this black support, issuing a crucial $8.2 million in bonds that released federal funding the following year (NC Civic, n.d.).

A 1968 map by the Durham Redevelopment Commission overlaying plans for the freeway over existing neighborhood plans. Note the bisection of the southern Durham/Hayti area (Durham Redevelopment Commission, 1968).

The resulting decade of redevelopment and construction would lead Hayti’s population to fall 43%, with relocation efforts spreading residents to black neighborhoods elsewhere in the city. Relocated businesses lost their client bases, and average household income fell 3.2% compared to an increase of 24.9% for the county (Ehrsam, 2010). The new freeway cut directly through the main business thoroughfare in the neighborhood, and a promised commercial district for displaced businesses failed to receive federal funding (Brundage, 2005). By the time the freeway was finally finished in 1992, Hayti had been physically divided and economically destroyed. Urban renewal in its larger context succeeded in renewing Durham as a cultural center, but its economic success is more tenuous. Targeted areas like Hayti were taken advantage of for their politically vulnerable populations, and relocation efforts proved costly, delayed, and ineffective at providing economic mobility by simply adding density to other impoverished black neighborhoods (Brundage, 2005).

A view of Highway 147 circa 2008 as it passes through Durham from the southeast. This stretch of road passes through what used to be Hayti (Sagdejev, 2008).

The effects of the destruction of Hayti are still questioned today. Some former residents believe that the white business leaders were capitalizing on the opportunity to break up the autonomous black economy in order to shift their dependencies to modern shopping centers; others claim that the politicians and planners targeted poor black communities because they lacked the political power to resist the government’s plans (Brundage, 2005). More generally, there is a consensus that the city never had much intention for the renewal project to benefit the areas affected by the highway construction; a 1963 survey of North Carolina redevelopment commissioners demonstrated this point, concluding that the state’s planning authorities had no “interest in or concern for the appearance of the sections of the cities to be rebuilt” (Brundage, 2005). These arguments have never been proven but illustrate the controversial nature of the project’s results. The question of renewal’s larger success in Durham is muddied by the collapse of Big Tobacco in the 1990s, forcing Durham to enter an economic identity crisis independent of its post-war decline.

A New Era, Though Not Always as Expected

Boston and Durham are two radically different cities, with dramatically different geographies, populations, economic dependencies, and cultures. Their programs of renewal took very different forms, with Boston’s West End being razed for middle class housing and Durham’s Hayti being divided to make way for new transportation infrastructure. The communities affected had different racial demographics but were similar in their tight-knit social relations. Their economic distress was visible in dilapidated housing stock and outdated infrastructures, but both provided a key public good to the greater city in which they were located. The programs that destroyed these communities shared good intentions of reviving a city in decline but held fault in their authoritarian oversight, targeting of politically vulnerable populations, and corruption by interests looking to profit off the process.

These two examples of renewal reveal a key insight in how city governments operate and the incentives that drive their decisions. In the cases of both Boston and Durham, a claim of what was good for the city according to the city (i.e. the potential for a revitalized tax base and all the services that might provide) came at odds with claims of what was good for the city according to its citizens (i.e. support for their communities). Arguments of the need for these communities to sacrifice for the greater good find contrast with arguments noting the equity issues of targeting marginalized populations and the conflicts of interest as a result of other capitalist interests intervening throughout the process.

The failures of the modern urban planning process have resulted in a new emphasis on recognizing the need for input from all parties affected and involved, not simply according to traditional hierarchies of political involvement according to power, race, and wealth. Reforms in planning recognize that the vocabularies of residents differ from the vocabularies of planners. The experiences that compose life in a neighborhood “resist objectification as verbal tracts, maps, or pictures” (Tuan, 1975, pp. 158), the bread and butter of traditional professional planners. The integration of this “local” knowledge with planner’s “scientific” knowledge presents challenges to the fundamental ways in which planners and policymakers operate but holds great promise in avoiding the authoritarianism seen in midcentury renewal (Innes and Booher, 2010).

The experiences of Boston and Durham serve as physical reminders of the legacy of planning. The processes of planners are unalterably intertwined with those of politicians and business leaders, and as such planning is inherently political regardless of claims of objectivity. The discipline has the unique capacity to see its theories and practices manifest on real landscapes, but with that comes the responsibility to understand how great of a power that is. The stories of Boston and Durham reveal the core questions defining planning– how should we plan? And for whom? These questions, deceptively simple, will continue to challenge and direct the profession as it faces the urban fabric of today.

Works Cited

Boston Housing Authority (1953). West End Project Report: A Preliminary Redevelopment Study of the West End of Boston. Boston, Massachusetts: Boston Housing Authority. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/westendprojectre00bost

Boston Redevelopment Authority (2015, September 25). “Exhibition showcasing past, present, and future of urban renewal opens at West End Museum”. Boston Redevelopment Authority. Retrieved from http://www.bostonredevelopmentauthority.org/news-calendar/news-updates/2015/09/25/exhibition-showcasing-past,-present,-and-future-of

Boston Redevelopment Authority (1960). “Aerial View of West End” [Photograph]. City of Boston Archives. Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/cityofbostonarchives/9322048248/in/album-72157634708439390/

Brundage, W. Fitzhugh. The Southern Past: a Clash of Race and Memory. Cambridge: the Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005.

Christensen, M. (2013). “Eminent Domain as a Tool for Redevelopment: a Case Study Analysis of Boston’s West End and New London’s Fort Trumbull Area” (Master’s thesis). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations Publishing (1547220).

Davidoff, P. (2012). “Advocacy and Pluralism in Planning”. In Fainstein, S. and Campbell, S. (Eds.), Readings in Planning Theory (pp. 191-205). Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing.

Durham Redevelopment Commission (n.d.). “Concerning Durham’s Urban Renewal Program” (Pamphlet). Durham Redevelopment Commission. Retrieved from http://library.digitalnc.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/durham/id/4010/rec/1

Ehrsam, F. (2010). “The Downfall of Durham’s Historic Hayti: Propagated or Preempted by Urban Renewal?”. Duke Journal of Economics, 22 (Spring). Retrieved from http://econ.duke.edu/research/journals-and-editorships/dje/volume-xxii-spring-2010

Gans, H.J. (1959). “The Human Implications of Current Redevelopment and Relocation Planning”. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 25(1), pp. 15-26. Retrieved from http://herbertgans.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/3-Human-Implications.pdf

Hebbert, F. (2007). “What they did to ‘the greatest neighborhood this side of heaven” [Photograph]. Retrieved from https://flic.kr/p/CeMSV

Innes, J. and Booher, D. (2010). “Chapter 7: Using Local Knowledge for Justice and Resilience.” In Planning with Complexity (pp. 170-196). New York: Routledge.

Kaliski, J. (1999). “The Present City and the Practice of City Design.” In Chase, J., Crawford, M., and Kaliski, J. (Eds.), Everyday Urbanism (pp. 88-109). New York: The Monacelli Press.

NC Civic Education Consortium (n.d.). “Durham’s Hayti Community- Urban Renewal or Urban Removal?”. NC Civic Education Consortium. Retrieved from http://civics.sites.unc.edu/files/2012/04/Hayti1.pdf

Roy Wenzlick & Co. and Durham Redevelopment Commission (1962). “Reuse Appraisal, Hayti-Elizabeth Street Renewal Area”. Durham Redevelopment Commission. Retrieved from http://library.digitalnc.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/durham/id/396/rec/2

Sagdejev, I. (2008). “NC 147 winding around downtown Durham” [Photograph]. Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/North_Carolina_Highway_147#/media/File:2008-07-23_Morning_Durham_from_Fayetteville_St_over_NC_147.jpg

Tuan, Y.F. (1975). “Place: An Experiential Perspective.” Geographical Review, 65(2), pp. 151-165. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/213970

United States Census Bureau (2010). “American FactFinder: Durham city, North Carolina”. United States Census Bureau American FactFinder. Retrieved from http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk

Zhang, Y. and Fang, K. (2004). “Is History Repeating Itself?: From Urban Renewal in the United States to Inner-City Redevelopment in China”. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 23, pp. 286-298.