For many tourists, especially for me circa 12-years-old on La Grande Tour with the family, “traveling” pretty much means running around museums. Literally — running — since it’s painfully true that it would take six years to see the entire collection at the Louvre if you spent a token 30 seconds on each work. Your feet hurt, you’ve seen hundreds of religious paintings and marble busts, and even the fantastical stuff with angels and Neptune don’t really interest you anymore. Had I not been uh, twelve, on my last visit to Europe (which involved a wham-bam circuit of the Louvre, the Uffizi, the Rodin Museum and many others), the museum bars might have been pretty damn alluring.

Rome, of course, is famous for museums — the most famous of which right now are the subjects of our joint art-architecture studio project (including the Musei Capitolini, the Crypta Balbi, the Montemartini and of course, Cornell alum Richard Meier’s little layer cake, the Ara Pacis). I’ll skip the famous ones (for now) in favor of the well-heeled and “avant-garde” (more on this later) opening at Rome’s MACRO Museum.

My apartment mate and friend, Mike Lee, has been working for Roman artist Pietro Ruffo since last semester. On a side note, Mike shares with me profoundly good taste in bad music (Boston’s “More Than A Feeling,” Akon’s “Love in This Club,” etc.), unrelenting wanderlust, and a passion for languages. Mike’s boss, Ruffo, is currently exhibiting at MACRO a sculpture-installation-intervention that Mike had worked on. I went with the Trastevere apartment mates (whom we’ve been calling La Famiglia in a mostly non-mafia-ish way) to see Ruffo’s work.

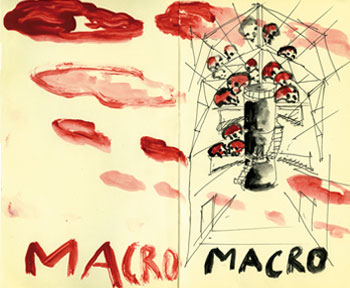

MACRO, Museo d’Arte Contemporanea Roma, is one of several modern museums that have taken over industrial sites (part of the Brooklyn-loft aesthetic that now connotes modernity and money). Upon entering — after fighting through a pack of young Italians in high-collared coats and older Italian women in furs — we were confronted by a tall nightmarish tower. Several stories high, made of jet black steel, ascending through artist Enzo Cucchi’s “Costume Interiore” was like stepping into the Nightmare Before Christmas or maybe a John Hejduk imaginarium, deserving of a name with capitals, maybe Tower Of The Suicide. With no apparent spaces for residence or inhabitation, ascending up wiry staircases left this visitor slightly disconcerted and touched by vertigo.

At the top, I made friends with a transgender woman dressed in a gorgeous fur coat who taught me how to swear in Italian. She smoked a hand-rolled cigarette to fight the queasiness (while we were, after all, indoors, albeit in a Rapunzel-ish location). We didn’t get each other’s names.

Two floors up, Mike’s artist, Ruffo, had his work paired with that of Valentino Diego in the same space — the two exhibitions were collectively called “Roommates.” Both projects were extremely physical. While in most museums, you’re able to wander from painting to painting, uninvolved and mostly unfeeling, in “Roommates,” both artists’ projects forced the viewer into engaging with the work. Valentino’s “Studio per DYnamic MAXimum tension” was a constructed ground plane of halved bicycle frames, forcing well-heeled visitors to step delicately across the room.

Ruffo’s “Nuovo Paesaggio Italiano” consisted of two paired, uninhabitable structures — maybe something out of Calvino’s Invisible Cities — under which were two mirrors. To see what the mirrors reflected, the viewer had to bend down and gaze below these fairy-tale-esque structures, revealing that inside them were suspended thousands of paper cockroaches swarming on geometric volumes.

While there is prolific installation art at museums in the United States, MACRO’s willingness to let people fully inhabit works — from touching them, to walking on them, and climbing inside and out of them — felt vastly different from the sort of hyper-sensitivity I’ve experienced at other museums. At the Calder exhibit in Rome, for example, sculptures that were meant to be moved and interacted with were set into motion with — literally — a ten foot long pole, swaddled with non-damaging padding and gauze.

At MACRO we were reminded that art and architecture are not just pictures on the wall (or in magazines) to gaze at — but rather works that can be appreciated with the same sort of physical vigor with which they were produced. The free Campari didn’t hurt either.