A coat made by the Crosby Frisian Fur Co., Rochester, N.Y., using the hide of the donor’s favorite horse, after it died. CF+TC #2005.64.084

Blog post by Ruby Jones ’22

*warning – this post contains images and descriptions of animal pelt processing*

I had no expectations about how I would spend my time in quarantine; yet still, when I found myself skinning a mink and tanning its hide last month, I have to say it was unexpected. Back in April, daunted by the empty five-month stretch ahead, I reached out to my professor in search of a research opportunity. We met over Zoom and she encouraged me to pursue a personal research project—something about which I was passionate—and on which she would advise. I wanted to explore the ethics of leather and use of fur in fashion in a way that considered nuances and complexities of the moral, environmental, and social implications. So often perspectives on fur in fashion are entrenched in black and white, either/or stances. We talked about different fur pieces in the Cornell Fashion + Textile Collection that might be considered more ethical: a fur coat from the early 1900s made of a favorite horse who died of natural causes and a pair of gloves from the same era, made of the hide of a well-loved family dog. While chatting with my professor, she challenged me to think about fur from my perspective as a designer and maker. She asked confidently, “Have you ever processed your own skins?”

Gloves made from the hide of a well-loved family dog after the pet passed away in 1918. CF+TC #1996.17.001

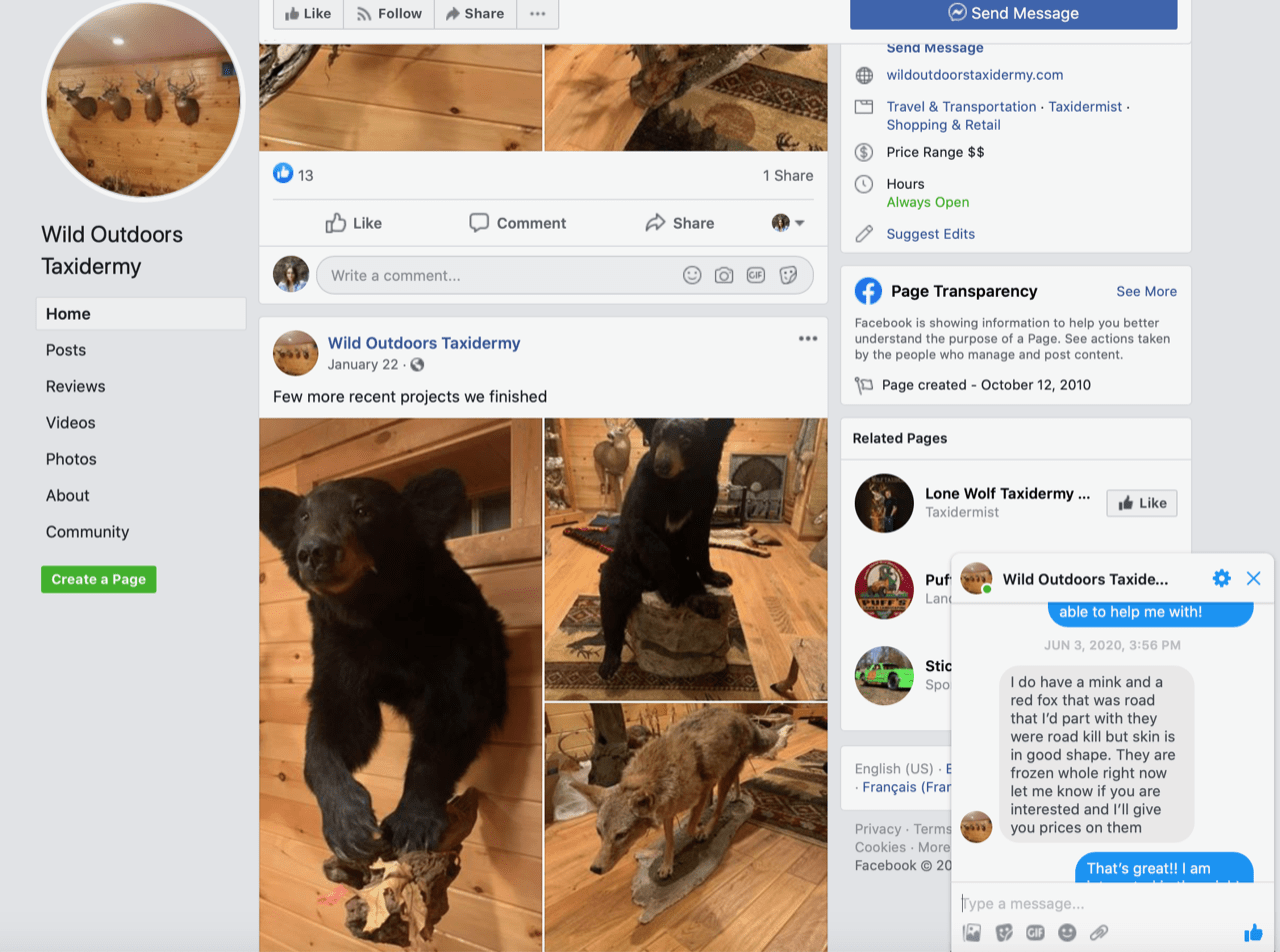

The question, at first, caught me a bit off guard. I have never been a hunter, and I certainly did not anticipate my fashion professor urging me to process a dead animal. With more thought, however, I felt incredibly grateful to have a professor who would even consider the project from that angle, and once the call was over, I became cautiously excited. My first task was to acquire an animal—small enough to manage, but not so small as to be insignificant in its challenges. As fashion design students and industry practitioners, we most frequently acquire fur and leather in a capitalist marketplace that sells it to us in abstracted form: beautiful pelts without faces or paws. While claws, faces, tails, and other animal body parts have been fashionable at different moments in time, today’s fashions mostly use the abstracted form. We do not often see the entire body of an animal on the runway, but rather the disembodied parts that are used as trims or entire fur coats in the fashion world. Having only been exposed to already processed fur, the idea of acquiring the entire body of a once-living being—complete with internal organs, a brain and skeleton—brought on many ethical questions. If I were to skin the animal myself, I would be faced with the body of a living being who died for fashion. But, what about salvaging animal hides that otherwise would be discarded? What about the possibility of roadkill? My professor recommended that I get in touch with a taxidermist or someone who might have a permit to collect roadkill, or perhaps a local museum or educational institution with vertebrate collections and who might have an “extra” sitting around in a freezer. Taxidermists, as it turns out, are not too hard to find, and I put out some feelers to all the locals through Facebook Messenger. (Cornell student, doing a research project, etc., and oh—happen to have any spare dead animals?) No one seemed at all phased by my request. “Wild Outdoors Taxidermy” had the best offer, asking whether I preferred a mink or a red fox. While both animals have been the source of many beautiful past fashions, I opted for the mink.

I had put in my order and was suddenly excited, anxious and feeling under pressure to learn what the heck to do with the frozen carcass when I picked it up. Despite growing up in a pretty rural area, my family of city transplants could offer no help. I used my research skills and internet-savvy to discover a plethora of information on the web, from the proper way to skin a mink (tubular fashion, starting at the hind legs, watch the scent glands) to various methods and commentaries on hide tanning (traditional, vegetable oil, failed experiment, don’t try). After fully immersing myself in mink-specific content and having one quite vivid dream (don’t watch skinning tutorials before bed), I finally felt ready. I drove thirty minutes to Wild Outdoors’ home address in Rural New York, and he greeted me, bag in hand. He was unexpectedly ordinary for a taxidermist—mid 30s, kids’ toys on the lawn, sporting an athletic team t-shirt—and after a brief conversation, he pulled “him” out to show me and handed me the surprisingly heavy mink and sent me on my way.

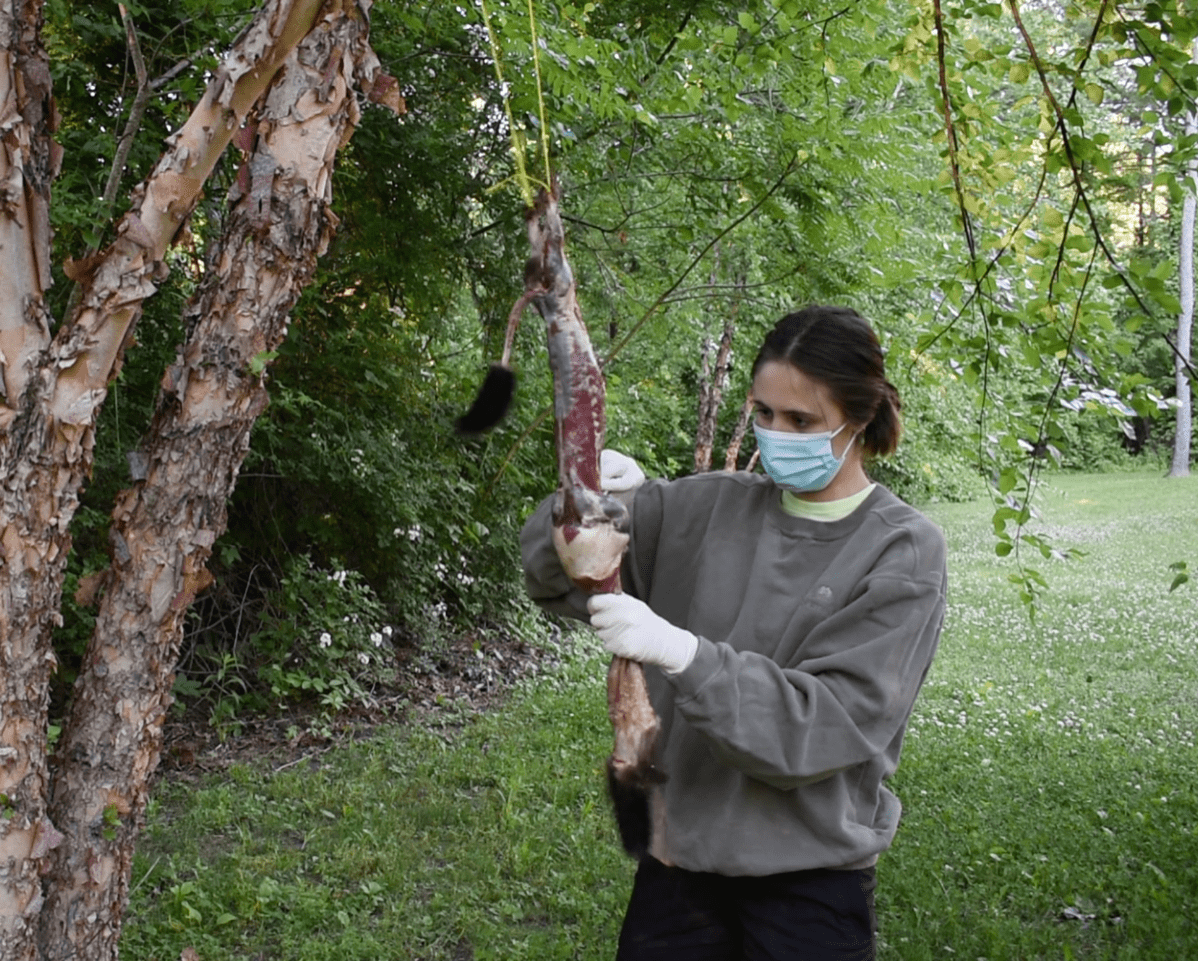

By the next day, the mink had properly thawed, and I set up my skinning station at a birch tree in my backyard. I strung him up by his hind legs, and with the words of the YouTube pros in my ears, I began. To skin a mink, you start by making cuts around each ankle. Cutting into an animal for the first time is a unique sensation; you don’t know how much pressure to apply, don’t know exactly what will lie beneath, and unlike store-bought meat, the animal is fully intact and lifelike. Nothing you can do will prepare you for the feeling of cutting through sinewy ankles for the first time. Once you release the feet, you draw a line from ankle to ankle, careful not to nick the scent glands. Then you extract the tailbone and work the legs out. The skin, rubbery in texture, begins to slide off. Small touches with the knife are enough to release the membrane holding the skin to the body. Before too long, the skin separates completely from the carcass.

Next comes the tanning. I had assumed the skinning would be the most challenging part of the project, but it did not compare at all to the multi-day preservation process. NBWildman, A Canadian trapper on YouTube making a “wall hanger for his brother’s camp,” guided me through the process. First you “flesh” the hide, manually scraping at the skin to remove any excess fat or tissue. If this step is not done properly, the hide will be stiff and will eventually rot. Then you salt the hide twice over a span of 48 hours, working the salt into the flesh, drawing out the moisture. You soak the dry hide in saltwater, rinse twice in freshwater, and scrub with soap to cut any remaining grease. Finally, you apply a tanning solution, and allow the chemicals to set into the skin. As it dries, you must knead and stretch the hide so it doesn’t stiffen. “And that’s a great way to preserve your trophies,” says NBWildman.

Tanning, in its essence, is about extracting an animal’s natural oils and replacing them with a synthetic, lasting substitute. It is replacing life with a preserved afterlife rather than natural death and decay. Carrying out this process simultaneously disconnected me from the living animal and gave me greater respect for its life. Once the carcass was gone, I was dealing with an object, a project, a task to be completed. I was scraping at a thing, processing it in various ways, “cleaning” it. Even in the act of literally removing flesh, the repetitive work put me into a meditative state, disconnected from the meaning of what I was doing. The respect for the animal’s life, on the other hand, built slowly throughout, and I think is something that cannot fully be realized without carrying out the process yourself. Present during the whole process are certain scents, sights, and textures that are uniquely animal in nature, and remind you of the complex biology, the life story, and the functional characteristics of the animal. I got to know my mink on a very intimate level. I saw exactly how, fundamentally, it was built to best serve itself, not me. The processes of skinning and tanning are not easy; the skin is deeply connected to the body it covers, and its removal is not something to be taken lightly.

Animal skins have unique sensorial properties of warmth, texture, and visual appeal. Those in combination with their biodegradability make them appealing for human use as a sustainable fashion. And while I don’t think there is anything inherently wrong with wearing skins, the consumerist system that supports their production is very broken. Hunting and farming of animals can come with exploitation, cruelty, and disregard for natural ecosystems. The highly toxic tanning industry is incredibly exploitative of people and planet across the globe. Exposing the industry is not what this essay is about, but in short, when animals are thought of solely as products and treatment of workers is driven by profits, any industry is bound to be destructive. I do not condemn the use of fur or leather; however, I do recommend that if you are going to wear animal skins, you do so with knowledge, reason, and intent. And, if you ever need a reminder of where your clothing comes from, consider contacting your local taxidermist.