A version of the following op-ed appeared yesterday in the Wall Street Journal’s Think Tank section of the Washington Wire. I am posting the slightly longer version of the piece here.

What’s an effective reaction to Islamic State’s destruction of artifacts housed in Iraq’s Mosul Museum and the militants’ bulldozing of the ancient site of Nimrud, former capital of the Assyrian Empire?

The barbarity of ISIS’s assault has provoked not just condemnation but also parody. One satirical Web site, the Pan-Arabia Enquirer, jokingly awarded ISIS a prize “for its conceptual art piece ‘Smashing Mosul Museum To Pieces: Death To The Infidels.’ ” The mock award praised the extremists for “demolishing priceless 3,000 year old statues” and said that liberating the works from “bourgeoise, middle class concepts of ‘beauty’ [had] invited us to examine pig ignorance as an artistic expression in itself.”

That critique is hard to beat. And it underscores a conundrum: ISIS is thrilled by the global outpouring of dismay. But shame has no power over the shameless. Moral condemnation has no impact upon those convinced of their moral righteousness. The extremists opened their program of defilement with acts against the bodies of opponents, journalists, minorities, and innocents; they have moved on to assaulting a heritage prized not just by Iraq but also by communities across the Near East and around the globe.

Assaults on archaeological remains, the durable parts of our historical memory, have happened for centuries, including in the area now threatened by ISIS. The 7th century BC Assyrian king Esarhaddon, whose palace at Nineveh lies across the Tigris river from modern Mosul, demanded that any vassal who violated his treaty obligations would suffer the defilement of the graves of his ancestors. But the wholesale destruction of a epoch of human history is something new. Even the Taliban’s widely deplored demolition of 6th-century colossal statues of the Buddha at Bamiyan seems surgical compared to ISIS’s reported bulldozing of entire archaeological sites. Irina Bokova, the director of UNESCO, has described ISIS’s campaign against antiquities as a war crime, a “cultural cleansing” that attempts to eradicate all diversity by destroying the evidence of history.

So how can the world effectively react to ISIS’s assault if outrage has reached the limits of its efficacy? The most powerful rebuke to those who would force us to forget the past is to redouble our commitment to remembering.

The Iraq Museum opened its doors early as a retort to ISIS’s attempts at historical erasure. Other global museums should do everything they can to display the remains of the ancient world that have been preserved for future generations and, as much as possible, the specific heritage that ISIS has sought to burn. But museums are not enough. The remains of ancient Mesopotamia should be made visible everywhere, from neckties emblazoned with lamassu (Assyrian deities often depicted as colossal winged bulls or lions with human heads) to a television marathon of documentary films dedicated to antiquity. If you are shocked by ISIS’s assault on antiquity, go take an archaeology class—in person or online—and become another who can say, “I will remember”. If media are the chosen vehicle for ISIS to transmit its program of shock, they are also critical to a global response. On at least this issue, defeat for ISIS lies in global memorialization, in a refusal to forget the past that extremists seek to destroy. A renewed exploration of the ancient world would be a direct rebuke to the depravities of those who would impose ignorance.

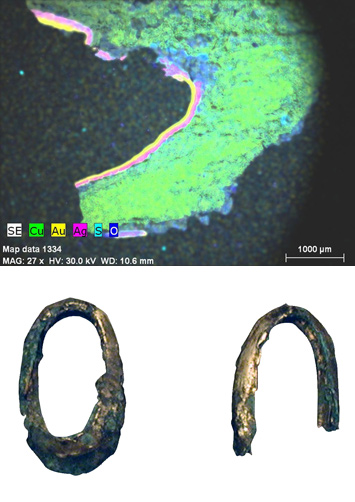

A recent article in Archaeology Magazine details recent work by David Peterson (Idaho State U) on a remarkable example of depletion gilding on a pendant from the Late Bronze Age

A recent article in Archaeology Magazine details recent work by David Peterson (Idaho State U) on a remarkable example of depletion gilding on a pendant from the Late Bronze Age

The innovation here is that the bust was not found within the borders of the Republic of Armenia and spirited out of the country to feed the colonial appetites of the British public (a la the Elgin Marbles). Instead, the bust was found in what is today northeastern Turkey but had been since at least the early 5th century BC part of a territory named Armenia.

The innovation here is that the bust was not found within the borders of the Republic of Armenia and spirited out of the country to feed the colonial appetites of the British public (a la the Elgin Marbles). Instead, the bust was found in what is today northeastern Turkey but had been since at least the early 5th century BC part of a territory named Armenia. Souren Melikian has an excellent review of “Islamic Art” at the Met

Souren Melikian has an excellent review of “Islamic Art” at the Met