A rising chorus of voices, mostly emanating from the Republican congress, has been stridently attacking research and teaching in the liberal arts. The assault on research has been led most persistently by the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, led by Rep. Lamar Smith. On February 10, the Committee released a press release decrying the use of taxpayer money to support projects ranging from archaeology and anthropology (my disciplines) to literary studies and history. The problem, they suggest, was that such research does not help create jobs or new technologies. Not surprisingly then, the attack on teaching has tried to pit the liberal arts against the so-called STEM fields, suggesting that only the latter foster the skills students need to get jobs and benefit society. As presidential hopeful Sen. Marco Rubio put it last November “Welders make more money than philosophers. We need more welders and less philosophers” (NYT 11/11/15). One thing is clear, Rubio’s campaign could use a grammarian or two.

The Republican case for less of the liberal arts and more technical training seems to arise from a profound misunderstanding of “skills”, those abilities that we cultivate through education and deploy in the course of a lifetime. Smith, Rubio, and others possess a surprisingly narrow understanding of skill, limited solely to a single job. Skill in welding is an excellent thing and can secure a job. But a successful welder might well decide to start a small business, for which very different skills are needed. Education in welding would not be enough. What if that business had international aspirations? That would require still other skills. And after not just a job, but a career, perhaps our welder might enter politics to serve the public good. Does that not require still more skills beyond welding?

Two things are surprising about the blinkered sense of skill embodied in Republican attacks on the liberal arts. The first is that they value job preparation over career training. The latter requires a far more diverse array of skills than any single technical aptitude. The second is that the jobs they want to prepare citizens for do not include preparation to lead the country as citizens or public servants. In other words, many of our leaders want students to be prepared for a job, just not their job.

It is a fundamental tenet of modern democratic politics that all citizens must be prepared not only for a job, but for careers that will demand a lifetime of many different skills. We must train our students how to understand the human condition (anthropology), to assess the importance of the past in contemporary problems (history, archaeology), to think about the relationship between general solutions and particular problems (philosophy), and to encounter humanity with empathy for others (literature, arts, etc.). In doing so, we also prepare them for a lifetime of citizenship, arming them with the tools to assess the claims of those in power, evaluate the programs of those who seek it, and reflect upon their own ability to contribute to the common good. It would be quite fitting then if one day a student of the liberal arts took Mr. Smith’s or Mr. Rubio’s job, since neither of them appears to understand the preparation required.

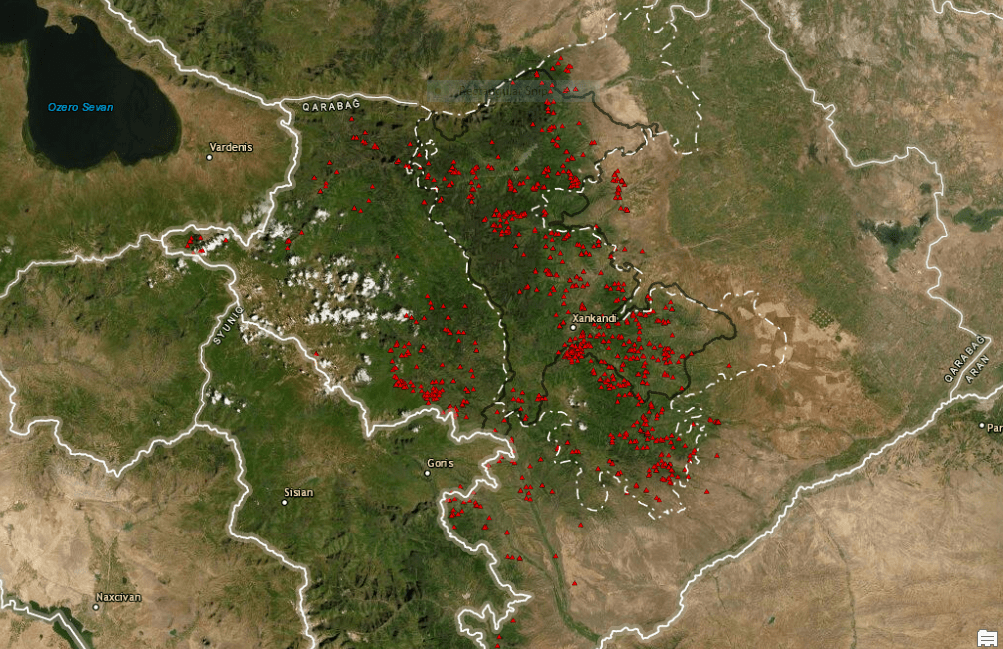

Caucasus Heritage Watch is

Caucasus Heritage Watch is

Here is an opinion piece that Lori Khatchadourian and I just posted on Cornell’s Medium blog entitled “

Here is an opinion piece that Lori Khatchadourian and I just posted on Cornell’s Medium blog entitled “